By pioneering a form that paved way for a renewed art appreciation in the country, Junyee has become a creative force to be reckoned with since the 1970s.

(Tatler Philippines) In celebration of his presence in the local arts scene for over 50 years, the so-called “Tatay” (Father) of many artists today took a visit to an exhibition dedicated to his legacy. Together, we looked back at some of his important milestones, his insights, and realisations that he wants to impart to the new breed of artists.

Luis Enano Yee Jr., who is more commonly known by his pseudonym Junyee, has been based in Los Baños, Laguna for most of his active creative life. He is the first of his generation of artists who braved mounting an exhibition of works made out of indigenous materials and in a wide scope of areas. Being the father of Installation Art and Indigenous Art in the country, nature was both his canvas and material. At the height of Modernism challenging the so-called “school of Amorsolo” to best express the tumultuous socio-political period of the time, Junyee emerged as a social realist artist fighting for the preservation and conservation of the environment and a voice of the oppressed by the dictatorial regime.

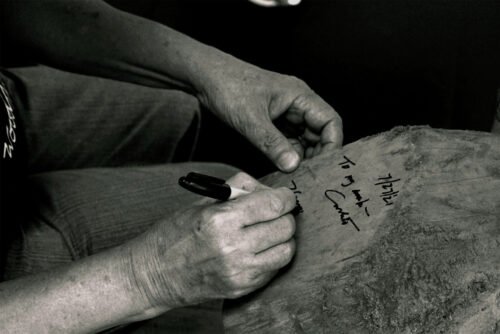

Luis “Junyee” Enano Yee Jr. / Image courtesy of the Cultural Center of the Philippines

Born in Agusan del Norte in 1942, Junyee moved to Metro Manila to study Fine Arts at the University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman. One of his mentors was Napoleon Abueva, who was dubbed the Father of Modern Philippine Sculpture and was later conferred as a National Artist. His Mindanaoan heritage has been evident in his art even today, and perhaps, it was one of the key things that made him break conventional and conservative art forms and use organic and indigenous materials for his site-specific works.

“I was born an artist,” he said when I asked him how his passion for the arts came about. “My early memories [include me] making drawings,” he recalled. “I joined my first art competition at a school art contest when I was nine years old, and I won first prize.” Junyee attributes Michaelangelo, the renowned Italian artist from the Renaissance period as his most influential teacher. “[But] I was not influenced by his works. Instead, of his passion in doing them,” he said. Indeed, Michaelangelo and Junyee share the same relentless spirit. Both made gargantuan masterpieces with such intensity and emotions, defying the conventions of art, as well as the powerful individuals in control of the people, of their eras. “But my constant teacher is nature,” the artist quickly said, picking up memories from the farthest corners of his mind. Indeed, he made a mark in the country’s contemporary art scene by building installations that are made of, inspired by, and speaks for, the environment.

More From Tatler: Purita Kalaw-Ledesma: The Woman Who Changed The History Of Philippine Art

In The Creative Legacy of Junyee write up of Riel Jaramillo Hilario, the author wrote, “This keenness to work with organic elements, upcycled refuse of the plant world, or the opportunities presented by the environment set Junyee apart from the rest. No one paid attention to the ravages of global warming 40 years ago. And yet Junyee, on his own, pursued this direction.”

Besides his longstanding career in the Philippines, his body of work includes his participation in several international exhibitions like the 12th Paris Biennale in 1982, the 4th and 7th Havana Biennale in 1991 and 2000, and the Asia Pacific Triennial in 1993, Australia. Last 2020, the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) gave him its highest accolade, the Gawad CCP Para sa Sining (CCP Award for the Arts), making him the first Mindanaoan artist to earn such recognition.

His lasting legacy on Philippine art dates back to his historic installation at the UP Diliman Campus. Entitled, “Balag“, the massive trellis made of bamboos and tree branches awakened the students’ and art connoisseurs’ notion of art as they finally see a masterpiece made of indigenous material in an outdoor setting away from the white walls of a gallery. And it was not for sale.

“My friends expected me to do a sculpture for my first one-man show because I have [received] awards in sculpture and it was also my major in college. In my first coffee table book, Wood Things, [I wrote there that with Balag] I answered a burning question of my time during my college days of ‘what is Filipino art’. I went back to nature to help me articulate my answer,” Junyee explained.

More From Tatler: 8 Of The Most Instagrammable Museums In Asia

I survived hunger and homelessness because to be an artist was, and still is, the burning pursuit of my spirit. It made me stronger and strangely more creative.

— Junyee

Another momentous installation art of Junyee was “Angud” in 2007, which was a landscape of numerous tree trunk parts where holes were drilled in order to haul the log from the mountains. They are considered junk, being the discarded part, and could no longer be sold. It was a protest installation Junyee mounted at the front of the CCP lawn.

“A social realist artist is one who speaks for the people who have no voice to speak their aspirations and dreams,” Junyee said. “It’s more than just defecting in canvas of their mysteries and hardships. I’ve been doing installation art in the social realist vein, and to do it, one has to dig deep in the experiences of how to be an underdog and down in the ring of social standing.”

An archival photo of Junyee’s “Cluster of Light” (2016) / Image courtesy of the artist

A photo of the artist’s “Bird of Fire” (2021) artwork made of soot and paint on board, similar to his 2012 “Dark Matter” series