Women on Women

Start

08 March 2012End

30 March 2012Artists

Agnes Arellano, Christina Quisumbing Ramilo, Delphine Delorme, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, Jenny Cortes, Katrina Pallon, Lina Llaguno-Ciani, Lydia Velasco, Marika Constantino, Sheen Ochavez, Valeria CavestanyGallery

Altro Mondo - Arte Contemporanea, 3rd Level Greenbelt 5, Ayala Center, Makati City

Almost Spaces

Adjani Arumpac

A group show with a full roster of women artists—a group show that calls attention to womanhood, to gender. Such focus on the subject matter poses but a couple of concerns. For instance: how can the artist claim her space of art production and recognition without over-determining gender, without assuming an alienating omnipotence, without conjuring the defensive/oppressive male/female conjunction—and all while keeping form at par with content?

These inquiries seem to be directed to the space inhabited by the production of art, rife as it is with limitations imposed by Superstructure conditionings. “Women on Women” is study on the possible ways and means to address these inquiries, the challenge, the concerns of art that explores and celebrates gender—womanhood, in this case—and its varied cultural significations.

A cursory look into the artists’ backgrounds, for instance, reveals that most have migrated out of or returned to their homeland. Here, then, the concept of mobility is set against a disparate set of works and profiles in an attempt to redefine femininity beyond the rigidities of the concept of place and its complex web of power relations.

Body/Society

In the eighties, Imelda Cajipe-Endaya, founder of Kasibulan (Kababaihan sa Sining at Bagong Sibol na Kamalayan), pioneered the use of indigenous materials in work that represents women’s liberation, gender issues, and ecology. This streak is evident inBigkis na Mapagpalaya (Ties That Bind, Ties That Free), made of acrylic on recycled wood, lace, sand, textiles, and found objects. Relying upon the physicality of objects to create an aesthetic experience, Endaya invites touch, action, interaction. She takes a jab at the conspicuous Christian icon of the Madonna by infusing ancient animistic patterns upon the mother and child in Anting-anting 2: Sa altar ng Anak and Anting-anting 3: Kalinga ni Ina, giving significance to a religion that has been brutally obliterated by the Spanish missionaries through centuries of persecution. Endaya operates within a construct of space that delves into the temporal. Her works, informed by her extensive research into regional folk art and Filipino printmaking since the 17th century, incorporate signs, medium, and historical narratives to create a rich discourse on Philippine identity.

In her series of coldcast marble reliefs collectively dubbed as the Virgin Apparitions, Agnes Arellano navigates through corporeal space. The artist unravels the myth of the Virgin through cloaked images, recalling the ubiquitous form of the benign Mary. Conversely, the form also recalls the female genitalia. Arellano has always explored the inviolability of the body—its painstaking transformations as its or her creed—borrowing embodiments from myths and religions as references, respectful but never wholly subscribing to these hegemonic powers. Virgin Apparitions is a confession on the inevitable aging of the body, when the carnal cannot hold and coitus is not a chief concern. The void created by this lack of libido becomes a space of contemplation, materialized by the artist as a literal transformation of sexuality to the internal/spiritual. Virginity, in this sense, is the piecing together of the body fragmented and violated by desire.

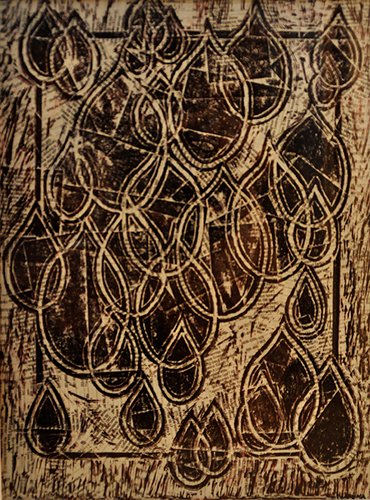

Jenny Cortes’ biomorphic pieces likewise negotiate body and society in wood sculptures that pulsate with life and sexuality despite their material. The foliar growths which she defines as “symbols of light, life, and giving” have already been seen in past works, their appearances more aggressive in the form of divans entitled Parausan, where she carves phallic forms on the seats to hint at intimate, unbridled female sexuality. However, the vulgarity of the forms is balanced with elegant execution, their dignity unquestionable with the curvilinear and smooth contours that make up precise and polished exteriors.

Home/Away

It’s interesting to note that the artists who have established identifications with two homelands display the most vivid colors in this collection. Valeria Cavestany is both a citizen of Spain and the Philippines, Lina Llaguno-Ciani shuttles back and forth between Italy and Philippines, while Delphine de Lorme is a French citizen who moved to Cebu, and has since established her studio in the province. These artists maintain a low-key presence within the local art world, their places arguably in the fringes and yet not quite.

Cavestany’s works are two sculptures made of iron sheet, painted with pastel colors, and pockmarked with tubelights. The two forms are random: one is an animal entitled Gazellen; the other, a watercan billed Estas Como Una Regadera (“you have more than a gram of craziness”). This is how Cavestany operates—her penchant for fusion correlates with a lighthearted, irreverent approach to the oftentimes too-serious art-making process.

Delphine de Lorme’s women—drawn flat and painted with flashy garish hues—recall old billboards painted by hand. The paintings, too, like the billboards, tell a narrative of desire with breasts and legs and orgasmic gaping mouths that shamelessly call attention to the displayed commodities of flesh.

Meanwhile, Llaguno-Ciani’s impressionistic strokes, her vivid but soothing colors, and feminine subjects reveal a fascination with the delicate and various shades of womanhood. Unrestrained hues and strokes, unapologetic rawness and a general sense of rough-hewn tenderness tell of a struggle to create not to conform to art institutions but to fill a gap of discontent. These artists present another side to the local art discourse—one which charts histories through the affections and compromises of the persistently mobile and unclassified.

Common/Dear

Christina Quisumbing Ramilo represents a departure from the group, both in choice of material and signification. Coming home to the Philippines after a long stint abroad, she arrived at a time when their home was under construction. Overseeing the construction work, she took notice of the painstaking process of rebuilding spaces that hold memories and identity. A newfound respect for the everyday inspired Ramilo to use what was available then—cigarette butts littered on the floor, discarded sandpaper, pencils, and other found objects. Her method of putting together found objects is purely aesthetic, more often than not working solely on the poetry and rhythm created by repetition of the material. And From Your Lips She Drew the Hallelujah plots the effort exerted in another kind of creation—the intensity and meticulous nature of the toil made visible by the varying shades created by plaster, paint and rust that had clung to the papers. She employs the same principle of repetition inCoco Rouge, with used cigarette butts. Ramilo’s inclination to the commonplace is a means of dealing with displacement upon coming back to a space that is quite and yet not quite home.

Sheen Ochavez is in a similar space as Ramilo, having constantly relocated in the past years. Her persistent search for residence translates as the naked female body in her canvases. She puts the nude women in spaces divided by unsure lines and suffused by vivid tints, as if portraying an undecided stimulation in gambling to find home in strange and stranger places.

“Women on Women” explores these traces of movement of the artists to look into and search for unbounded spaces wherein free inquiry into the underlying social processes can be genuinely facilitated. Places—liberally defined here as status, situation, identification—is redundant in the modern world, wherein circulation is a necessity for survival, where everywhere is a compound of overlapping mobilities. To erase place is to negotiate the paralyzing urgencies imposed by the body, community, home, and affections. It enables the artist to determine oppressive tamings and from these deductions, create works that are more self-reflexive. To truly determine constructions of identities and affinities to better inform and innovate works, women artists must continue to find the female in between addresses, in transit.