Why Am I Always The One Packing Up My Stuff?

Start

09 November 2019End

02 December 2019Artists

Faye Pamintuan, Poeleen Alvarez, Tammy De RocaGallery

1159 Chino Roces Avenue, San Antonio Village, Makati City

The exhibition, “Why Am I the One Always Packing Up My Stuff?” presents how the three female artists reflect on the years as they transition from childhood to adulthood. Taking their cue from a comment made by a character in Sofia Coppola’s 1999 adaptation of Jeffrey Eugenides’“The Virgin Suicides”, where a male doctor tells Cecilia that she’s not even old enough to understand how bad life gets as she lies on her hospital bed. Cecilia then easily quips even in her moment of vulnerability and tells him, “Obviously, Doctor, you’ve never been a 13-year-old girl.”

Perhaps, the intensity and intimacy of the stories behind the works in the exhibition may overlook or justify the formation of how an artist becomes an artist (or interpret as creating a spectacle out of our own little personal histories that do not matter in the wider sense of the world). However, what we have here are images and forms derived from the only way we know how to tell what it’s like being a 13-year-old girl and the years that follow marking their coming of age. “Why Am I the One Always Packing Up My Stuff?” considers female narratives that are told without any apparent representation of the female figure. Instead, the exhibition flourishes on the reconciliation of memories built from time, place, and feeling as expressed by the artists.

In Poeleen Alvarez’s “Small Pond”, the town of Obando, Bulacan is at the center of the artist’s recollection. Remembered for its perennial flooding as much as it is celebrated for the local community’s miraculous fertility dance, the artist’s hometown is situated on a strip of land caught in between several urban towns and the Manila Bay. Alvarez’s work is an illustration of how she fears the looming construction of the Bulacan Aerotropolis – an urban utopia set to be built on reclaimed marshlands, to completely eradicate and place her hometown underwater. Here, Alvarez uses unfired stoneware clay to make a cast of eroded cement, which is a visual representation of Obando; weathered by water in increments through time. With the clay shaped after the map of Obando, a separatory funnel and retort will stand to simulate the rhythmic dropping of water, reminiscent of an hourglass. The process is captured on video and combined with a collection of clips taken around the town throughout the years.

Tammy De Roca’s large installation is a visual representation of how the artist struggled to initially remember her state at the height of her transformation to adulthood. De Roca realizes that in doing so, she forcefully suppresses these thoughts and memories due to traumatic experiences. The artist then, creates works that resemble fragments of her inaccessible past resulting in a work that appears like a shiny void.

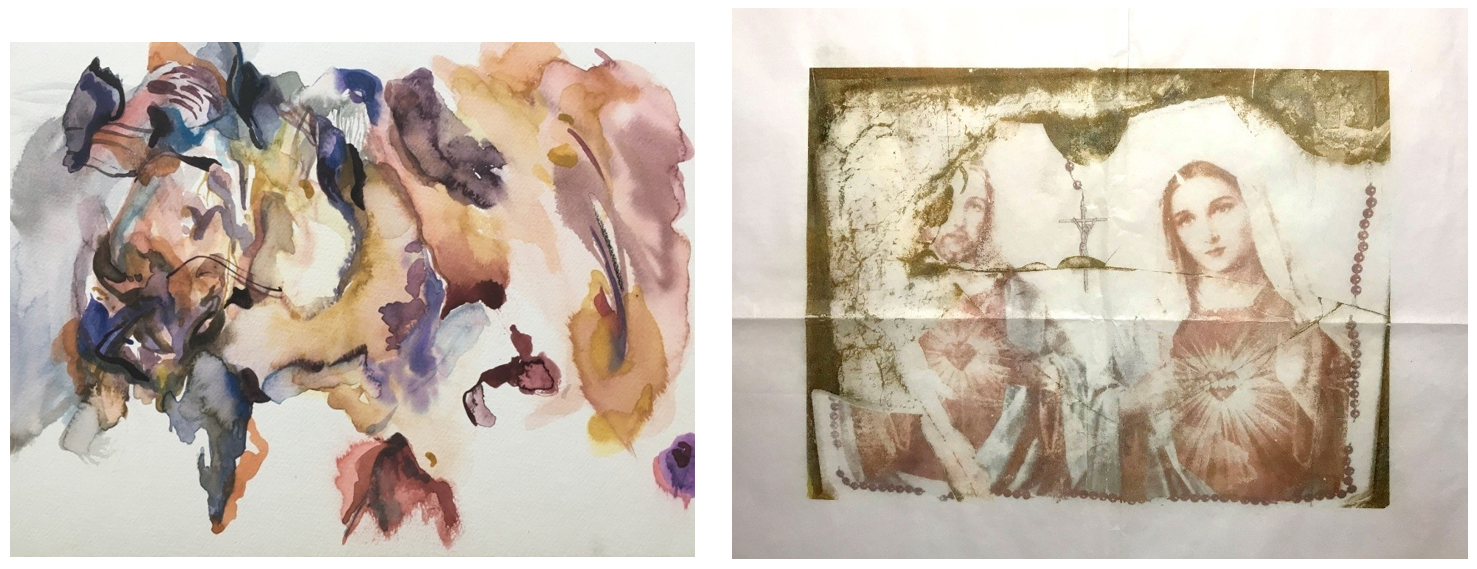

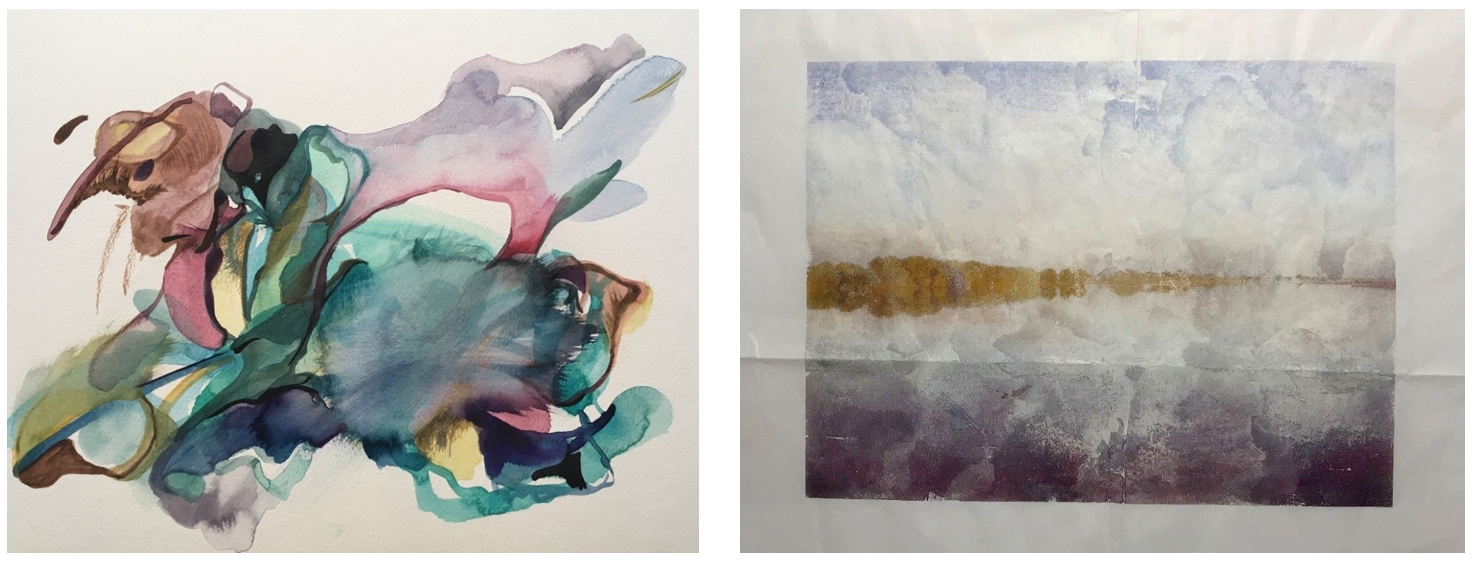

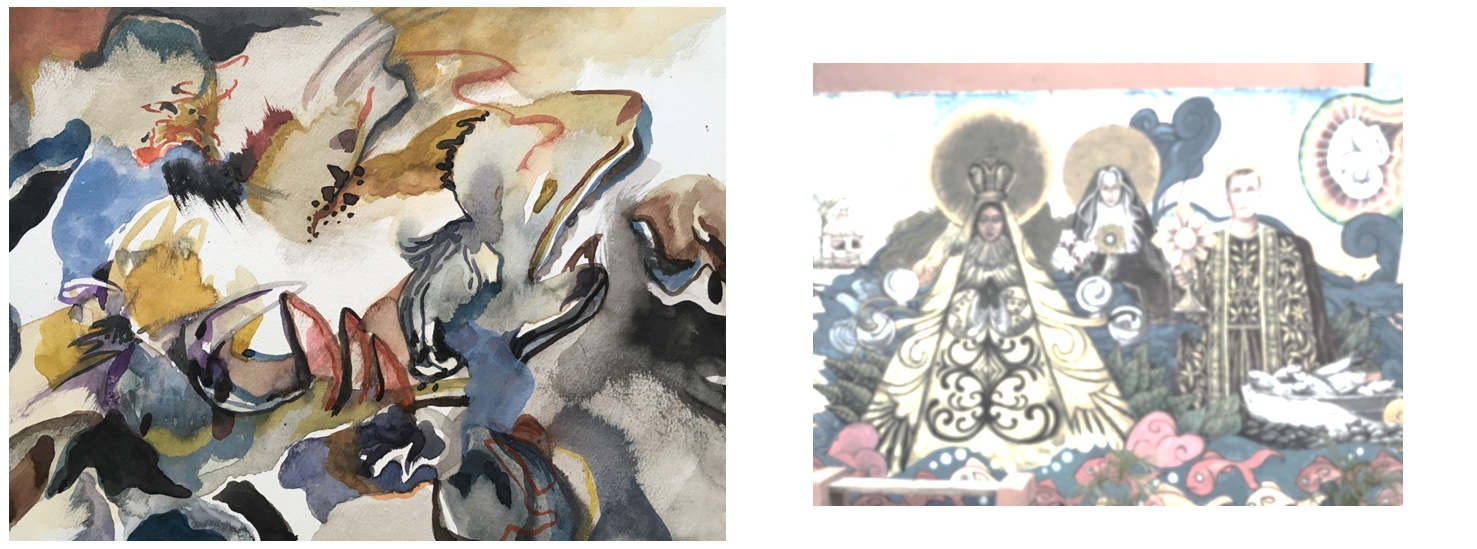

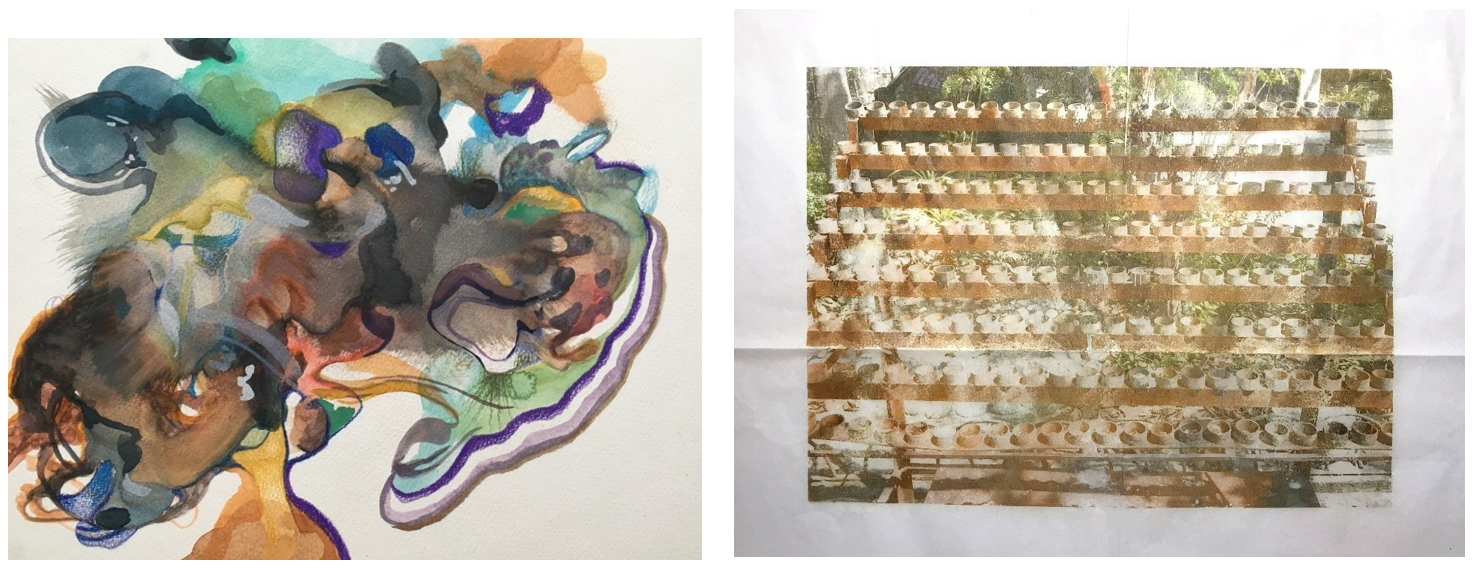

Faye Pamintuan’s watercolor paintings combine the two places where she lived through her coming of age years (Texas and the Philippines) into an imagined landscape. Here, landmarks and images suggest the intervention of identity through illustrations of fences, posts, and suggestive walls. Through her shaped works on paper, Pamintuan executes control in the way she brings together her history by mapping her own sense of self and completely taking charge of how she would reveal parts of her life through marking and cutting the watercolor paper. Living a life in between two different countries, Pamintuan’s transformation to adulthood notes a journey that encompasses immigration and repatriation.

In another series, Alvarez and Pamintuan, who both call the province of Bulacan home, collaborate on a visual journal that seeks to chronicle their parallel childhood years. Here, Alvarez’s photographs of her neighborhood are translated by Pamintuan in abstract forms; a way of considering what the latter’s childhood might be like if the conditions were different and she didn’t have to migrate to the United States. A sort of pacification is found among the images that the two artists present in the exhibition thriving on nostalgia and in looking back at something missed or lost.

Lastly, we would like to dedicate this exhibition to the loving memory of Tracy De Roca (1997 – 2019).

– Gwen Bautista, Curator