Roaring It

If in the 1920s, fine art exploded to a spectrum of unbridled new styles in the west, today’s Philippine paints seem to implode onto one installation canvas a series of diverse contemporary trends. The artists couldn’t have timed this implosion better, as new galleries continue to sprout across the metropolis and growing talk of art auctions in town find accommodating ears.

Not unlike the artists of the vibrant Deco and Dali era, the participants in this survey of early 21st century Philippine art appear determined to prove through oil and acrylic that their concepts are neither simulacra of Western-inflected traditions nor mere retellings of a People Powered past. The call is for the world outside their discipline to recognize that their pieces are not mere designs, but upon scrutiny, are efforts at mature architecture built on individual insight and culture.

Ironically, in their mission to be au courant of this post-effing-everything generation, a number of the participants in the assembly (re)turn to the human form. Two artists in particular have been known to make use of the classical figure as a stark means of conveying social themes. Joel “Welbart” Bartolome employs his patented white-masked nude in “The Portrait of Mr. Clay.” Whether it’s driven by political commentary or personal redemption, or both, the figure here awaits truth or the final opportunity to conceal the same. Though it appears that life depends on the scene that follows, the composure of the subject remains unflinching—recalling chiseled sculptures left to the elements in Greek sights protected by UNESCO—though he is grounded as well within a humanistic perspective. There is also Anthony Mallari’s even more classical nude. In the artist’s version of the Venetian school’s angels, a child who has died of poverty ascends against an eschatological sky. Worth noting is how Mallari has drawn her wings, as if she had been born with them underneath her flimsy rag.

A number of them also reference modern art’s distortions, mutilations, sublimations, though none are intoxicated with Baconian sensibility and historical concerns. Bjorn Calleja makes a blur of the body. Jeric Sadullo reveals a warrior/worker’s reedy but sturdy wiring. Rodelio “Toti” Cerda’s “My Sacrifice” centers on a tattoo of a peace sign at the back of a man poised for execution. Mideo Cruz places a kitschy mirror over a soldier’s stance, recalling Magritte. Gromyko Semper’s “Allegory of the Meta (physician)” is a figure captured in a Greek mythological god’s pose, holding up a light bulb egg.

It’s as if there’s a movement to respond to dated criticism that young contemporary artists mustn’t opt to forego classical mastery, fail to acknowledge the importance of figuration, before they can be permitted in their practice to critique and dislodge. The underlying principle seems to espouse that the artist’s inner workings and environs (as opposed to codified origins) are where solid material lies and art of some profundity have the hope of arising from. The body is not intended to function as device, isn’t treated for the most part as dictum, emblem, or legend toward didactic impulses. It is instead molded out of, at times fragmented among, often uncovered and framed within, the interiors of both one’s suffering and means of emancipation. Sometimes, it is reduced to a cacophony of brushstrokes and its hand amid the apocalyptic, as in Jigger Cruz’ piece. In other studio samples—“Abuse Me” by Jessie Mondares and “Pinarata” by Joey Cobcobo—even its standard metaphors of all that ails have been blown indistinguishable.

In one piece, it screams itself back to a pulse in the hopes of respecting vision again, as in Calleja’s one-eyed creation. For the image’s directness (what’s one more scream in contemporary art?), the body’s refusal to carry the burden of anyone’s other than its own renders necessary, not gimmicky, the bold disjunction in a child’s crayola colors.

Other works triumph to similar extent in belying claims that today’s young artists and apprentices have the unjustified impulse to confound without enough regard for tradition, and are generally careless in their alchemic displays. The ones that do rely mostly on the painter’s convictions translating well through a combination of mentored impasto and intuition while shedding adolescent self-consciousness and an underlying need for mainstream approval. Perhaps the most significant contributions in this respect may be those that avoid late 20th century preoccupation with debasement and utter annihilation in favor of irony and humor, once faced with impossible quandaries and the unlimited catastrophes of a globalized age.

Dexter Sy’s “Half Day Closing” and Orly Ypon’s “Conundrum” are a couple of such works. They exemplify the curious blend of ambiguous rhetoric and compositional aesthetics that affirms the presence of genuine feeling from plumbing deep into the process. These artists have no interest in gestural or “clever” dialogue, though it is often the easier route to question the ultimate relevance of Sy’s pop-playful art or distrust the necessity of Ypon’s realist approach on the particular subject.

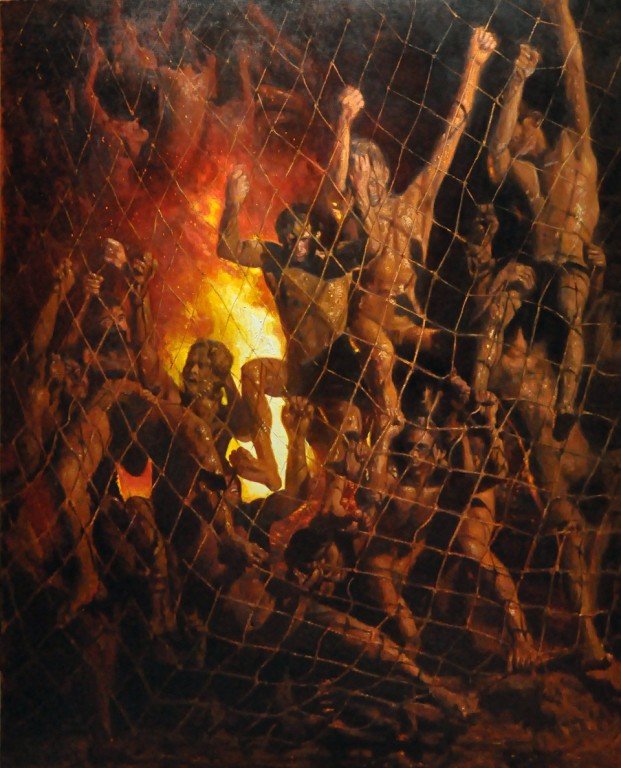

Whatever the judgment on these meticulously executed strokes, it appears that the more units attend the canvas, the stronger the work informs on the subconscious. Sy opts for a group trapped in Commie-red and other vivid comic book colors in dissecting conventional notions on death, which on a daily basis gets buried in a variety of self-gratifying distractions. If this is indeed hell, then the artist (the nude composed of literal inner demon), is the last in line to burn—the horned wards and tormenters have long inhabited his system. Ypon’s intuitive realism on the other hand, proves that in authentic work, there’s more than intense emotion that gets expended on the canvas. Somewhere among the toothless mud blobs of his hell (or is it purgatory?), there’s wit and weltanschaung, which are also endangered. It is also worth noting, given the artist’s staunch realist style, that with this composition, it can be said he is influenced only circuitously by photography. Limb and torso remain remnants of “Solarium” training.

Though the pieces appear in profusion to abstract and dismember, assemble then fragment, there are a couple which seem to have been jolted by a single galvanizing event. These focus less on contemporizing a style and more on plainly sampling a point in history or myth not often depicted, or once retold, tend to become lobby wallpaper. Juanito Torres paints the onset of Limahong’s battle with Spaniards in CCP-familiar tans and yellows, then punctuates the frustrated struggle with a domestic dog. Tom Daquioag’s “Sa Ngalan ng Bayan” features his staple costumed characters, though he seeks to eschew the cliché traps of satire by lightly portraying Pinoy foibles alongside heroic efforts. Marcel Antonio’s “Promethean Rising” infuses the myth with Latin American magic realism and billboarded soap drama, as he has been known to do.

For the most part, however, the works lean toward unfinished progressions to underscore their makers’ unwillingness to conclude via impasto. It’s admirable that they are mostly ambiguous, but never truly ambivalent—as evoked by inspirations which are as much varied as Pinoy culture is storied and subsequently robbed of memorabilia. As Calleja remarks in one of his interviews, “we all are products of our environment, we are the sum of all the people, places and events we have encountered in our lives.” This is best illustrated in one of Noli Manalang’s “Across the Universe” delights. In this version, the artist’s appealing triptych format shows more symmetry in the collage, suggesting karmic forces, though not necessarily conclusive judgment. There’s a dynamite (with a crucifix for a lock) in the palm at the bottom of one panel, and a corresponding hand on top of a skull midway through the opposite panel. This is the lone piece that directly addresses technology, which itself floats like a trademark above the whole grand scheme of things in the form of a simple @.

What proves most exceptional about the Roaring 20 and more is that their very ambitions continue to be articulated maturely with time and interdisciplinary thinking. Manalang polishes his reportoire without glazing over raw idioms, sounding off his own voice. With weighty wooden shutters, Semper now presents a choice, an interpretation, instead of providing dichotomous versions in one panel (though one could argue this literary juxtaposition has been a source of strength and thrill). Calleja pushes his usual surreal distortions, and abstracts further to finally let out a scream.