Remnants

Start

29 August 2013End

14 September 2013Artist

Niccolo JoseGallery

Altro Mondo • Arte Contemporanea, 3rd Level Greenbelt 5, Ayala Center, Makati City

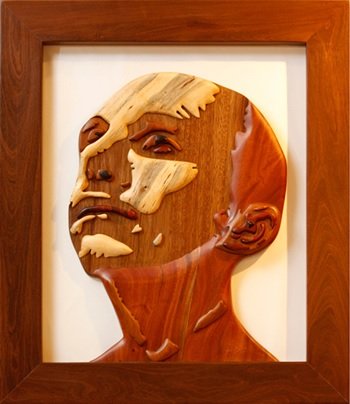

The human forms in Niccolo Jose’s Remnants are not anatomical. Rather, human anatomy is artistically suggested, gestured toward rather than illustrated.

What we see in Jose’s artworks is therefore the abstraction—rather than the representation—of human anatomy—its parts and interiors that, in the image, seem to have been brought up out into the light for exposure and inspection. Some of these, then, are the most unusual nudes that one can see, as the stripping of the human body is more than just a matter of absent textile. In these artworks, the inside is literally the outside, and the blur of the distinction is brought to solid, dramatic effect with the unlikely material of wood.

Many other artists have done the same artistic gesture of abstracting and suggesting human anatomy; Francis Bacon, of course, is the exemplary figure in the subcategory, having worked with x-rays in order to limn the body’s insides while keeping clear of illustration. But apart from the interest in the human body as imagery, Jose’s art, of course, in no way resemble Bacon’s. For one, instead of the Baconian sense of motion, what we see—and crucially, experience as a sensation—in Jose’s art is a monumental, stone-like stillness. Although supple in terms of shape, Jose’s works are remarkable for an implacable stillness that borders on a drama of immobilism. And lest one think that these human forms are tortured, it must be noted that such immobilism evinces a kind of peaceful, almost homely repose.

A straddling of opposites is Jose’s consistent modus operandi. Interior and exterior are presented in the instant. The human and the vegetal occupy the same zone. The hard edge and the soft form—opposites—harmonize within his pictorial frame. Also, a kind of graphic simplicity that is reminiscent of the imagery of Pop Art is placed in tension against the organic, honesty of wood: industrial meets natural.

Most of all, however, it is the simultaneous use of figuration and abstraction that is remarkable. The collocation of the abstract and the figurative, their interplay in these works, shows an unexpected cooperation toward a single image that is astounding. Viewed up-close and in parts, Jose’s works appear to be a species of Arp-like abstraction as shapes of wood, almost invariably round and always smooth-edged, are layered and cobbled together as to form a composition that creates, through a remarkable absence of either movement or narrative, a desire in the eye to rove toward the rest of the artwork.