Klaro

Start

07 June 2012End

30 June 2012Artists

Camille dela Rosa, CJ Tañedo, Edrick Daniel, Gerry Joquico Jr., Gromyko Semper, Jericho Vamenta, Lester Rodriguez, Noli Manalang, Ronaldo RuizGallery

Altro Mondo • Arte Contemporanea, 3rd Level Greenbelt 5, Ayala Center, Makati City

Un/veiled

T.C.M.

“IT BEGAN WITH NO ADO,” was how Annie Dillard remembered the eclipse. The American writer, known for her essays and fiction, travelled to Washington, Oregon one morning in 1979 to witness a total solar eclipse.Without pause or preamble, silent as orbits, a piece of the sun went away,” Dillard writes. The cosmic event transformed the surrounding landscape, washed it with all the wrong hues, with alien light. “What I saw,” recounts Dillard, “what I seemed to be standing in, was all the wrecked light that the memories of the dead could shed upon the living . . . [e]mpty space stoppered our eyes and mouths; we cared for nothing. We remembered our living days wrong.”

Consider what happens in an eclipse: the moon travels between the Earth and the sun. A total eclipse leaves only a tiny ring of light in the sky, smaller than “half the diameter of a dime held at arms length,” to refer to Dillard’s accounts. Day turns into night, and everything seems to turn into something else. The familliar is dislodged, the veneer of known reality is peeled away, and there, underneath, another emerges.

The sun was going, and the world was wrong. The grasses were wrong; they were platinum. Their every detail of stem, head, and blade shone lightless and artificially distinct as an art photographer’s platinum print. This color has never been seen on earth. The hues were metallic; their finish was matte. The hillside was a nineteenth-century tinted photograph from which the tints had faded . . . [t]he sky was navy blue. My hands were silver. All the distant hills’ grasses were finespun metal which the wind laid down. I was watching a faded color print of a movie filmed in the Middle Ages; I was standing in it, by some mistake.

–Annie Dillard, “Total Eclipse”

The moon is bright and full in Edrick Daniel’s “The Hunter,” and yet the woods are dark and dangerous. A character oft-seen in his works stands in this scene: the rabbit-heart. Taking note of how the shape of the little creature’s head resembles a human heart—how the rabbit itself, small and fearful, signifies the heart—Daniel constructs a figure that, in past works, served only as pet or companion to his humans. This time, the rabbit takes on human form. It takes center stage. It takes its fate into its own hands. The meek and fragile conceals itself in a disguise, gun in hand, turns into a predator: but one which, still, has predators of its own. One which, despite the costume, the attempt to redefine itself, stands there wary rather than aggressive, more whimsical than threatening, awash in inviting pastel colors. The transformation reveals yearning and fear: how one may lead to the other if given the chance.

The series “And He Shall Be Called Wo-man” deals with costumes as well. Camille dela Rosa decks her canvas with ethnic motifs and feminine hues. The gowns and adornments on her subjects—indigenous priestesses called babaylans—are just as lavish. By the gesture of trying to hide it, the artist calls attention to it: that these priestesses are, in fact, men. One’s jaw, the other’s nose, the arms betray masculine features. Delving into native culture, the series reveals what colonialism has concealed: that women held a powerful position in native communities; that transvestism was sacred and ceremonial, not comical. Men were allowed to conceal their gender, dress as the opposite sex, and assume a role deemed crucial in a society.

Ronaldo Ruiz perceives what is unseen and yet ubiquitous. Paired with a human body, vessel of action, life, motion, change, the inert and unobtrusive reality of the table becomes both stage and subject, bearer, witness, and accomplice to human struggle. Stripped bare, table and man shed identity and context. It is a simultaneous act of un/concealment. The man on the table becomes a curious spectacle that stands for no one man and for everyone.

Gerry Joquico’s paintings dwell on the intersections between memory and imagination. He obscures what is remembered with what the passage of time has replaced it: figments of imagination, make-believe images that arise out of the need for reinterpretation. “Desnudado Andres” presents a snapshot of childhood, rendered nostalgic with sepia hues. It is entirely possible but for the oddity of the dog-headed figure. Here, the the artist reveals that imagination can resonate with the essence of experience more than a vivid reconstruction of reality.

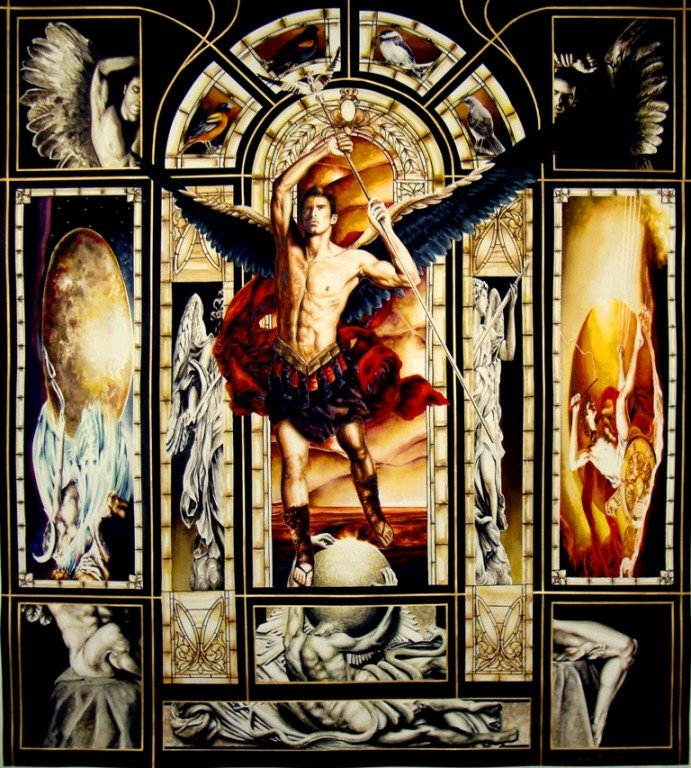

Jericho Vamenta’s “Puerta Himaya” reveals but not quite, conceals but not quite. It is a threshold, a “doorway,” an in-transition. Winged male deities hold a curtain half-draped over a naked woman grasping a basket of flowers to her breasts. “Himaya,” in Bisaya, means a state of bliss and glory, of being carried away by the weight of it. Here, the woman tilts her head up, as if in expectation. There is something yet to come. It may be her coming-to-greatness, a being-born, her unveiling. But it may be the end to it as well, the descent that follows the zenith of any upward trajectory. What is revealed, here, is a prevarious instance of vulnerability.

One reality is obscured, another surfaces. A revelation occurs in an act of concealment. The dialectic between the two polarities arises in the act of expression: what is illuminated, in the end, is their inseparability. Here, clarity does not precede perception. It is not a requirement as is light for sight, as is, perhaps, logic for reason. Here, clarity is destination: a product of perception, of the collision and coherence of contrary forces.