begin with the second, a mirror of the first

Start

08 January 2022End

12 February 2022Artists

Andre Baldovino, Christian Culangan, Floyd Absalon, Gabe Naguiat, Gelo Narag, Jopet Arias

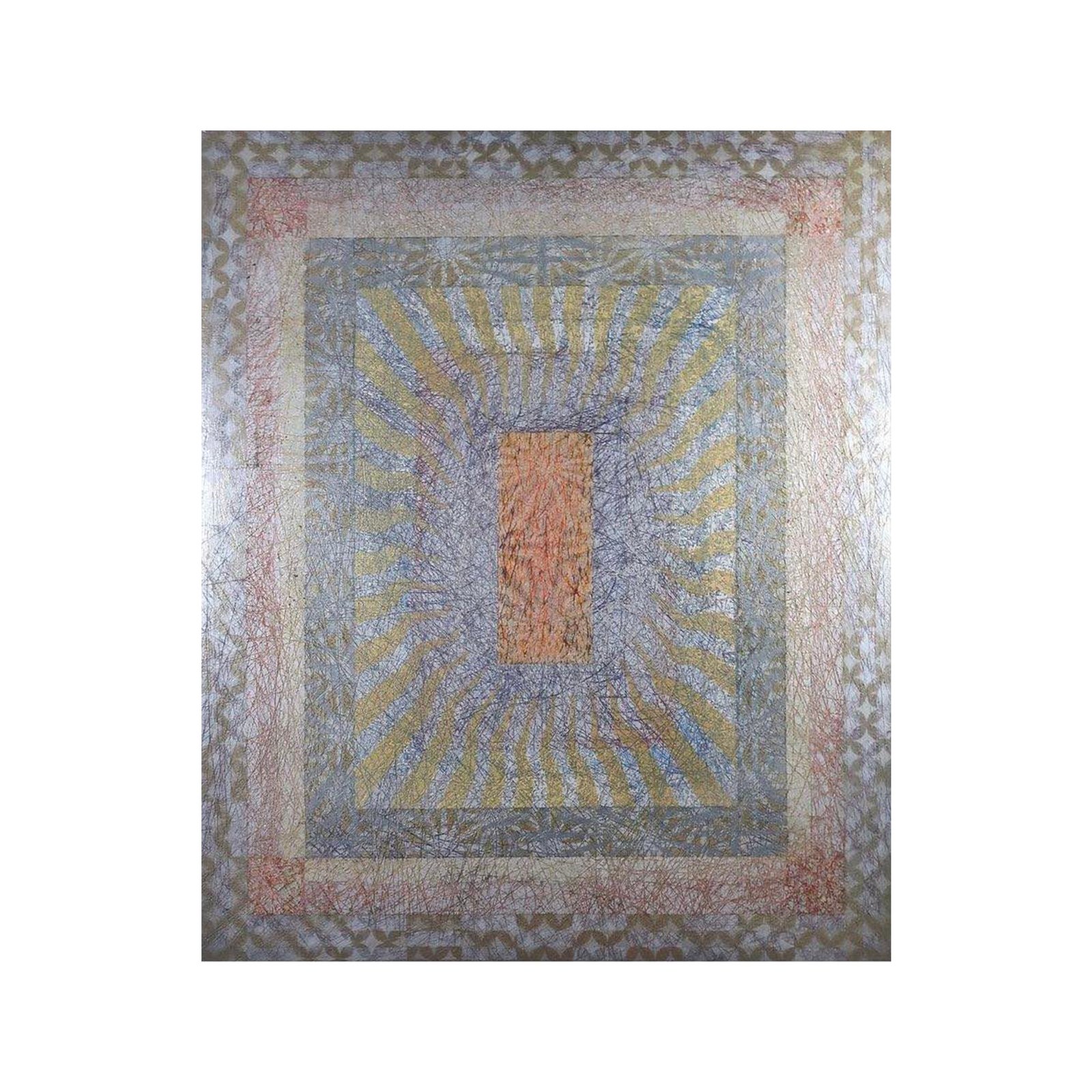

I Split an Image into Two, but Still Ended up with One

It is quite uncommon to find a concept that connotes a beauty that straddles multiple disciplines despite extreme differences between them. Mathematicians see it on either side of equations. Physicists see it as they study microscopic and macroscopic universes. Poets see it in the way words interact. Architecture puts great consideration into its existence in every aspect of the built environment. This is the value of symmetry in the human experience and this is ever so true when it comes to Art.

Children are trained to master shapes like circles, squares, and triangles in early art classes, and later on growing up entails the need to mathematically bisect them at the least (with many questioning the purpose of such a skill). Most, if not all of us, learn to fold paper in half: the beginnings of a paper plane, a paper boat. For some it will evolve into paper cranes or any of the advanced techniques origami has to offer. Yet it all begins with turning what was one into two.

Two. A pair. A human pairbond is such a valuable relationship. Out of all humans, out of the countless personalities, traits, idiosyncrasies, or even genetic mutations, to find another human being that seems to have that perfect reflection of ourselves is most likely a once in a lifetime phenomenon. It exists between friends, lovers, family members, and pets – but the destruction, the severance of this bond can shatter to such degrees that the beings involved are never the same, never whole again. Because it is such: two halves of a whole, two sides of a coin; or a binary – left and right, black and white, yin and yang – it only makes sense in juxtaposition, being side by side in an intangible symmetry.

And yet after all that has been said until now, it is not a binary, or not simply so. It might be that there are a variety of symmetries: rotational, radial, translational, bilateral, reflection, among others, but they all begin with a second, a mirror of the first. One that has always been considered whole, is actually two halves of a complementary image. And then it expands both ways: broken down into smaller components, or building upon itself. Going back to the circle, square, and triangle – most of the complex things around you right now can be reduced to these shapes, as symmetry does not end with just two parts.

A study by Sasaki Yuka and colleagues (2005) found that the visual cortex is activated better by symmetrical visuals, while many other studies have shown that human aesthetic preference has a predisposition to be governed by the symmetrical. However, even the human body, in its apparent bilateral symmetry, bears a multitude of nuances. Some things are slightly lower on this side, bigger on that side. Unfolding a paper crane reveals a delicate yet captivating array of lines, not all of which appear on the other side. At this point it should be obvious that symmetry is also about the relation of parts to a whole – considering how the Golden Ratio explains the way symmetry works in either reduction or replication.

In her seminal essay “Reading the Image,” Alice Guillermo discusses the relationship of figures or elements in a work, how these “occur in temporal sequence to constitute a narrative or may take the form of simultaneous facets or aspects of reality.” However intentional, there will always be a layer of subconscious, even of the mystical, in how these relationships turn into images. Eventually given a purpose to understand the elements that form any symmetry as a metaphor, each of the artists in this exhibition partake of a whole and split the images in their minds as they explore personal symmetries.

— Francisco Lee